The Voynich Manuscript Decoded?

I give examples to show that the code used in the Voynich Manuscript is probably a series of Italian word anagrams written in a fancy embellished script. This code, that has been confusing scholars for nearly a century, is therefore not as complicated as it first appears.

All attempts over the past century to decode this mysterious manuscript have met with failure. This is probably due to the initial error made by Voynich and his followers attributing the authorship of the manuscript to Roger Bacon, the 13th century British scientist, monk and scholar. As I showed in a previous paper on my Website, The Voynich Manuscript, was the author left handed?, Roger Bacon could not have written this manuscript and I suggested that a young (around 8 to 10 years old) Leonardo da Vinci was a likely author. Using this premise I proceeded to consider what would be required to decode this manuscript and reached the following conclusions:

- Determine the language used in writing the manuscript

- Correlate the Voynich alphabet with the modern English alphabet

- Decipher the code

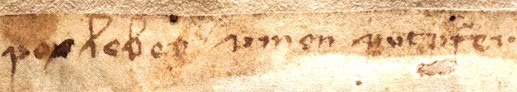

If Leonardo da Vinci was the author of the VM, he would have used the language of Dante, i.e. medieval Italian, so I have assumed the VM language to be Italian. I initially used Rene Zandbergen’s basic EVA characters(i) as a starting point to correlate the VM letters with the English alphabet, while taking into account that the Italian alphabet only uses 21 letters. Later in my studies I had to modify some of the EVA correlations. As the best code breakers, using powerful computers, were unable to decipher the code, it did not appear likely that I could break the code. I am however addicted of solving Jumbles and playing Text Twist and this made me consider a different approach. When I examined the VM script, I noticed that there were very few corrections, and the writing, though slow, had the appearance of easy fluidity. A complicated code would require making a preliminary copy using for example a slate for a scratch pad. Paper was expensive in the 15th century. To produce a 200 page manuscript under these conditions would be a very tedious task. The encoding must have been simple, easy and direct. Gordon Rugg(ii) has suggested that the VM is nothing but a meaningless jumble of letters! I wondered whether he was not correct, with one modification, only the individual words were jumbled, i.e. anagrams. I was further encouraged when looking at the last page, Folio 116v of the VM to find that the top line on this page is:

The Italian alphabet does not use the letter X. Leonardo used this letter as shorthand for ver.(iii) This line may be interpreted as follows:

Which translates into English as follows:

This brief sentence indicated that the use of anagrams should be investigated. This was further supported by reading Wikipedia’s report that anagrams were popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and that some 17th century astronomers, while engaged in verification of their discoveries, used anagrams to hide their ideas. Thus Galileo announced his discovery that Venus had phases like the Moon in the form of an anagram. Similarly Robert Hooke in 1660 first published Hooke’s Law in the form of an anagram.

Word anagrams do not always offer a unique solution and an exact collelation between the EVA characters and the English alphabet has not been established, therefore, to test this ‘anagram hypothesis’ as precisely as possible, I used the single words found on many of the herbal pages. Most of these drawings are so poor that the author of the manuscript obviously considered it necessary to identify the roots/plants with names. I therefore used these single words to help modify the EVA alphabet (shown below) based on the plant/root name obtained from the subsequent translated Italian anagram. This resulted for the most part in a usable correspondence between the VM and English alphabets which when once established was used for deciphering all subsequent anagrams. I quibble a little here for at this time I have not been able to identify all the 21 letters of the VM Italian alphabet (j,k,w,x, and y excluded). The letters H, Q, Z and a single T have not been identified and there may also be some letter combinations like that used for tl that need to be identified. The ll combination may represent either one or two l’s. Letters like o and a, when they occur at the end of a word, have a tail and can easily be confused with a g, which has a curved tail. Other letters like m,n,r and u, when they occur at the end of a word have a curlicue. It is difficult to interpret words that have a number of c’s and e’s. These anagrams are best solved by trial and error. The letters I used from the VM and their English equivalent are shown in the table below:

Using this basic alphabet I have identified a number of plants, herbs and vegetables from the herbal pages. I was not able to decipher all the words, due no doubt to the fact that many of the plants around 500-plus years ago probably had common names that have since fallen into disuse. In addition modification in the spelling of some words may have occurred making it difficult for someone like myself, who does not read or speak Italian, to decipher these words.

I used an Internet site, ‘Italian Anagram Dictionary,’ to help me unscramble the words and translate the anagrams into English. The book ‘The Botanical Gardens of Padua 1545-1995’(iv) helped identify some of the common names used for plants in Italy in the 16th century. You can judge from the examples given below, whether this Anagram Code has been successful deciphering this limited selection from the Voynich Manuscript. I hope some of you who read medieval Italian will help decipher more of the manuscript so we can finally learn the mysteries, if any, that this manuscript is hiding.

When I gave this manuscript a final reading, I suddenly remembered that Dan Brown in his book ‘The Da Vinci Code’ made use of anagrams. It will be ironic if Leonardo da Vinci is established as the author of the Voynich Manuscript and it is accepted that he used anagrams for his code. I doubt however that the Voynich Manuscript will have much to say about Mary Magdelene or the Priory of Sion, but that remains to be seen.

The pages that follow contain sections of the Voynich Manuscript with words that have been decoded using the anagram method. The first line of typed text above the Voynich handwritten text is the modern English interpretation of the letters. The second line is an Italian anagram of these letters. The third line is the anagram translated into English.