Bartolomeo Marchionni and the Afro-Portuguese Ivories

The first trade goods from West Africa to be sold in Europe were the Afro-Portuguese ivories, exquisitely carved spoons, forks, saltcellars, pyxes(1) and oliphants(2) that are found today in museums in Europe and America. Photographs of these artifacts can be found in the book Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory.(i) Bassani and Fagg, the authors of this book have divided the ivory carvings into two groups. They suggested that the single chambered saltcellars, some of the spoons, forks, pyxes and oliphants were carved in Sierra Leone(3) during the years 1490 to 1530. The double chambered saltcellars, some spoons and a few oliphants were carved in Benin some time during the 16th century.

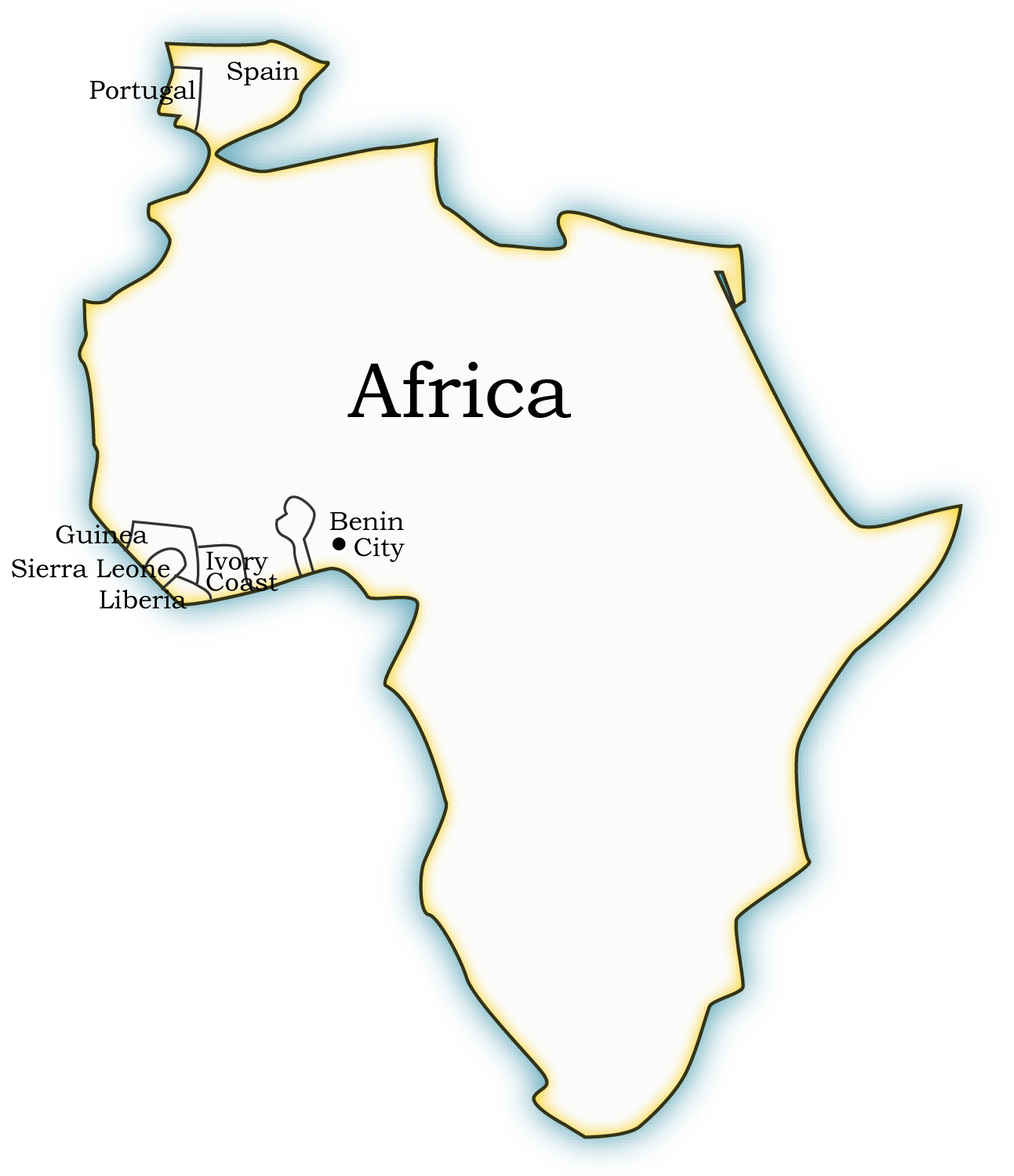

The map shows that although ivory was available along the entire Coast of West Africa, the Afro-Portuguese ivories came from only two African countries, Sierra Leone and Benin, separated from each other by a considerable distance. In the late 15th, early 16th centuries the Portuguese established trading stations at strategic points along the West Coast of Africa. What was there about Sierra Leone and Benin during the early days of Portuguese trading that differed from the rest of West Africa? In 1480, the Portuguese King, John II, sold the right to trade slaves, spices, and elephant tusks from Guinea to Bartolomeo Marchionni, a wealthy Florentine banker and merchant in Lisbon, for forty thousand crusados.(4) Sierra Leone, situated on the Atlantic coast of Africa, was at that time included as part of Guinea. This license was extended in 1486 to include the Slave River in the Gulf of Benin and was further extended to 1495 in return for 6.3 million reis(5) for each year that Marchionni held the contract.(ii) King John II followed by his nephew Manuel, maintained control of the trade between Guinea and the Gulf of Benin, where they had located a steady supply of gold at Elmina. The Portuguese were mainly interested in gold, slave trading and in finding a sea route to India. Marchionni had established an extensive network of agents and clients that extended from Portugal to Spain to England, Flanders and Italy. His influential patrons included the Kings of Portugal and Spain and associates from Florence, like Lorenzo de Medici.(iii) He was the dominant trader in slaves from West Africa. Slaves he obtained from Benin were traded with the African gold merchants at Elmina for gold. Those he could not sell were taken to Madeira to work on the sugar plantations or to the slave house in Lisbon for sale in Europe.

There is no question that an artist or artists from Europe were involved in training the African craftsmen from both Sierra Leone and Benin to carve ivory artifact for sale in Europe. The German scholar, Wilhelm Foy, suggested the possibility of a workshop in Portugal where the Afro-Portuguese ivories were made under the guidance of European artists.(iv) Fagg initially stated that: “The majority of these curious and beautiful hybrid works were made by carvers from the Sherbro area of Sierra Leone, a much smaller number, perhaps a quarter of the hundred or so known pieces, were carved by Bini trained in the style of the Igbesamwan;(6) there is internal evidence to show that the Portuguese recruited fine carvers from both these tribes and set them to work together somewhere on the West Coast, or more probably in Portugal itself, in late 16th century”(7)(v) Later, Bassani and Fagg discounted this proposal due to the discovery of 16th century documents showing that ivory spoons and saltcellars were among the goods that sailors brought back from Africa.(vi) However a strong case can be made, on the basis of the hazardous health conditions that existed for Europeans living in or visiting Benin in the late 15th century, for the initial training of Bini artists in Europe. Benin lay within the tropical rain forest of West Africa where tsetse flies, malaria and other parasitic diseases were endemic. One famous rhyme went:(vii)

Beware and take care of the Bight of Benin;

Few come out, though many go in.

Benin City is about 60 miles inland from the coastal mangrove swamps of the Bight of Benin and not far from the many creeks and estuaries of the Benin River that lacks a suitable harbor for large ships. The Portuguese king obviously kept the most profitable trading area of West Africa for himself and leased the two end pieces to Bartolomeo Marchionni.

It would be logical, for skilled carvers to be trained at the same school, rather than set up individual schools in Sierra Leone and Benin. Later these trained carvers could return home to work and train additional artists, thereby increasing the availability of exotic artifacts for sale in the European markets. When the carving of these ivories began, Bartolomeo Marchionni controlled the trade from both Sierra Leone and Benin and he may have instigated the setting up of a workshop to train these African artists. Employment with the powerful Marchionni organization would offer an impoverished European artist not only financial security but access to some of Marchionni’s influential patrons. Artists in the Renaissance were regarded as artisans and many led an impoverished existence. Marchionni had relatives and friends from Florence in various countries available to act for him promoting his business interests. If he employed someone to train African artists, that person probably came from Florence.

The very nature of the Afro-Portuguese ivories, spoons, forks, saltcellars, pyxes and oliphants (hunting horns) clearly indicate close European supervision. Thanks to the extensive investigations of Bassini and Fagg, the pictures used for the designs carved on the hunting horns offer additional clues as to the location of this workshop.(viii) The designs came from books printed in France and northern Italy at the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries and are as follows:

- St. George and the dragon from a Florentine woodcut circa 1495.

- The book of hours of the Virgin Mary printed by Philippe Pigoucher for Simon Vostre, Paris 1498.

- A woodcut from the 1493 edition of Commodium Rulalium by Petrus de Crescentis of Bologna (1230-1321). His twelve books on agriculture were first printed in Italian, Latin, French and German in 1471.

- The mark of the printer Thielman Kerver, Paris 1497

- The mark of the printer Antoine Verard, Paris 1485-1512

- Libro della ventura, Lorenzo Spirito, Milan 1500. He was an Italian poet and astrologer who wrote this popular Book of Fortune. This book was first published in 1482 and was so popular that it underwent numerous reprintings.

- Woodcuts by Albrecht Durer 1506-1510.

- Ovid’s Metamorphoses, first illustrated Italian edition 1497.

Books at the end of the 15th century were still a novelty and expensive. Whoever owned or had access to the above set of books had an eclectic taste in literature and was interested in a variety of different subjects. The person who owned these books was no ordinary man. In addition to being an artist, he could read both French and Italian. A trader going to West Africa might own a printed copy of the Bible or Book of Hours, but what use would he have had for a book on agriculture like Commodium Rulalium or woodcuts by Albrecht Durer? He could, as has been suggested, have taken sketches from these books with him to West Africa, but someone still had to provide him with the books.

Carved on some of the ivory horns are emblems relating the reigns of King Manuel of Portugal and King Ferdinand of Spain. Bassini and Fagg suggest that these horns were commissioned some time between the coronation of Ferdinand in 1492 and his death in 1516.(ix) The dates 1492 - 1516 correspond reasonably well to the publication dates of the books that supplied the illustrations used on these horns. That the books were printed in either Italian or French is not surprising as the Portuguese only began printing their own books in 1497, about forty years after the Italians and French. The printing press was invented in 1440. Gutenberg completed printing his first bible in 1455 and although by the turn of the century new books were being printed at a staggering rate, many Europeans were still illiterate.

The woodcut depicting “The hunt of the birds with a cross bow” from 1493 edition of Commodium Rulalium by Petrus de Crescentis(x) was copied on a hunting horn carved by someone from Sierra Leone. The mirror image of this woodcut can be found on a Benin plaque showing a Portuguese cross bow man shooting a long beaked bird possibly an ibis. An ibis is a long-legged wading bird with long down curved bill that built its nests in trees. The birds on both the plaque and the woodcut look like ibises. An illustration of the remnant of this plaque can be viewed in the book Nigerian Images.(xi) Another feature that the hunting horns made by Sierra Leone artists have in common with many Benin bronzes is the use of the guilloche pattern, known in Benin as the ring around the world.(xii) Plate 3 illustrates this pattern and is shown carved on a Benin ivory powder flask from my personal collection. The guilloche is a twisted rope design that was used to frame patterns in Roman mosaic tile flooring. Designs with two, three or even five interwoven strands were popular. This design may therefore have originated in Italy. Leonardo da Vinci who lived at the same time that some of the Afro-Portuguese ivories were being carved, was intrigued with this pattern and used it in his logo for his Leonardi Academia Vici.(xiii) Other artists who were associated with Leonardo may also have used this design. The presence of the bird hunt and the Guilloche pattern on both the Sierra Leone and Benin artifacts support the possibility that the same school trained both Sierra Leone and Benin artists and that given Marchionni’s penchant for employing friends from Florence, this school may have been in Italy.

It is not my intention to imply that all the Afro-Portuguese ivories were carved in Europe. An examination of the “Catalogue Raisonne” in Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory(xiv) will show that many of the pieces, particularly some of the saltcellars carved by Sierra Leone artists are typically African in design and may have been carved in Africa. In contrast, many of the hunting horns, or oliphants with their European designs may have been carved under the direction of a teacher or teachers from Marchionni’s organization. Some of the Benin double saltcellars were probably also carved in this school. Plate 2 is a copy of one of these saltcellars, except that this copy is cast in brass, and is considerable larger than the original, that was 29.2 cm in height. The ivory saltcellar was probably carved to commemorate Vasco da Gama’s successful return in 1499 from his first voyage to India. Before da Gama set sail in 1497, King Manuel of Portugal made him a Knight Commander of the Military Order of Christ and presented him with a Maltese cross. He is always shown in drawings or paintings wearing this cross round his neck. The long faced, hooked nose, bearded man with the cross on this saltcellar even looks like a painting of Vasco da Gama that can be found in Wikipedia on the internet. The other saltcellars in the Benin collection also appear to have been made under European direction.

Some time around 1502 or later, the Benin concession passed to Marchionni’s business partner,(xv) Fernao de Loronha ( Noronha) a Christian convert, who paid 1600 milreis per annum for the lease(xvi) He also controlled the pepper trade from both Guinea and Brazil.(xvii) This apparent change in ownership of trade with Sierra Leone and Benin probably had little effect on Marchionni’s trading activities in the area, he was still the major slave trader in West Africa and in 1510 supplied the Spanish king with the first West African slaves sent to the New World.(xviii) Most of the information relating to his West African activities are lost so it is only possible to surmise what affect Marchionni had on the people of the region. One thing is certain, all his interests were controlled by a desire to make money and please his wealthy and powerful clients. During the 16th century, Sierra Leone was invaded by a group of cannibals called the Sumbas, who after leaving their home in central Africa, had traveled slowly westward, destroying any tribe that stood in their way. Eventually, by about the mid 16th century, they reached the coast and subjugated the people of Sierra Leone. This ended ivory carving from this region, but in Benin, brass casting and ivory carving continued until the British Punitive Expedition in 1897, when the British destroyed Benin City and looted all their ivory and brass works of art.

If we accept the premise that this hypothetical teacher was an employee of Marchionni’s vast financial empire, then he was probably an artist from Florence who was experienced in both carving and metalwork. In addition to the Benin saltcellars, the Benin plaque, the bird hunt and other plaques by the artist designated by William Fagg, as “the Master of the Leopard Hunt,”(xix) may have been made in his shop. There were many workshops or bottegas in Florence during the late 15th century and many impoverished artists who would have been more than happy to earn a steady living. I assume that this hypothetical artist not only provided African trade goods for sale in Europe, but may also have provided goods for barter in Benin in return for slaves, ivory and pepper.

Portugal was a poor country with no manufacturing base. To trade in Africa and particularly the Orient required goods from Europe and not just manillas and beads. The Africans wanted luxury goods like cloth, silks, clothing, hats, metal utensils, horses and their trappings. The Portuguese prohibited the sale of firearms to any African chief who was not a Christian. The Asians and Orientals were different, they had little use for European goods, and required payment in gold, silver or ivory for the pepper and other spices and luxury goods they sent to the West.(xx) Marchionni sold slaves, ivory, spice, sugar and wine to different European countries. Although he has been described as the original Renaissance slave trader, he was reluctant to sell slaves to his Italian friends,(xxi) but some African slaves were sent to Pisa and Tuscany. Florentine merchants had a large carrying trade between Italy and Portugal. They imported fine woolen cloth, leather goods and silk into Lisbon and sold preserved fish, ivory from Guinea, cork and Moroccan leather in Italy.(xxii) Europe was one large commercial hub even if communication and travel were much slower than today. The Renaissance was an exciting time of exploration, commerce, art and learning.

- ↑ back pyxes - containers for keeping wafers for the Eucharist

- ↑ back oliphants - hunting horns

- ↑ back Sierra Leone - part of Guinea

- ↑ back crusados - Portuguese silver coin

- ↑ back reis - 325 reis was worth one gold cruzado

- ↑ back Igbesamwan - the name the Bini ivory carvers’ guild

- ↑ back 16th century - 16th century must be a typo, Fagg almost certainly meant 15th century

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich.

- ↑ back Blake, J.W., 1942, Europeans in West Africa, 1450 - 1560, Vol 1, Hakluyt Society, London, p.125.

- ↑ back Thomas, H., 1997, The Slave Trade, A Touchstone Book, Simon Schuster, New York, p.84-86.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich., p.57.

- ↑ back Fagg, W. and List, H., 1963, Nigerian Images, Frederick A Praeger, New York, p.39.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich. P.60.

- ↑ back Thomas, H., 1997, The Slave Trade, A Touchstone Book, Simon Schuster, New York, p. 360.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, p.95-122.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, p.109.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, p.105.

- ↑ back Fagg, W. and List, H., 1963, Nigerian Images, Frederick A Praeger, New York, Plate 22.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, p.100.

- ↑ back Richter, J.P., 1970, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Vol1, Dover Publications Inc., New York, p.361.

- ↑ back Bassani, E. and Fagg, W., 1988, Africa and the Renaissance, Art in Ivory, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, p.233-249. .

- ↑ back Thomas, H., 1997, The Slave Trade, A Touchstone Book, Simon Schuster, New York, p.105.

- ↑ back Blake, J.W., 1942, Europeans in West Africa, 1450 - 1560, Vol 1, Hakluyt Society, London, p.98 and 106. .

- ↑ back Thomas, H., 1997, The Slave Trade, A Touchstone Book, Simon Schuster, New York, p.111.

- ↑ back Thomas, H., 1997, The Slave Trade, A Touchstone Book, Simon Schuster, New York, p.95.

- ↑ back Fagg, W. and List, H., 1963, Nigerian Images, Frederick A Praeger, New York, p.22.

- ↑ back Lunde, P., 2005, Saudi Aramco World, Vol.56, No.4, p.58.

- ↑ back Black Africans. P.222.

- ↑ back Hart, H., 1950, Sea Road to the Indies, Macmillian, New York, p.51.